|

Several schools have asked about the interaction between ‘Scaled Scores’ (as reported following End of Key Stage tests) and Standardised Scores (as reported by standardised tests such as those provided by Rising Stars, GL Assessment, CEM or NFER). Whilst these scores look similar, most people in school are by now aware that they are actually quite different. Given the superficial similarity between scores reported as a Scaled Score of ‘100’, say, and a Standardised Score of ‘100’, it isn’t hard to see why.

Standardised Scores I wrote a blog for CEM which explains how Standardised Scores are created. As I said in the blog, ‘For nationally standardised tests, a mean and standard deviation based on a representative sample of the population will give an indication of a student’s position within the national population of those taking the test.’ This means that a Standardised Score of 100 tells you that the underlying test score is the same as the mean score on the test recorded by a reasonable national sample of those taking the test. Standardised Scores have various limitations, but in principle they are effective when it comes to ranking children against a reference group of children. They do not, however, give any information about the performance of children against a set of standards. Scaled Scores Scaled Scores as reported for Key Stage 2 are used to place children on a scale from 80 to 120. These scores are intended to provide a numerical indication of children’s performance, largely so that a Value Added calculation can be made to be used within the government’s accountability structure for schools. A panel of experts is convened to designate the raw test score which is deemed to indicate be ‘of the expected standard’. Anything above is higher than the expected standard, anything below is not. The raw scores are then converted into an 80 to 120 scale, where 100 is the ‘expected standard’. The tables for the most recent KS2 Scaled Score conversions can be found here. The government has muddied the waters a little more/made things easier to understand by introducing the terms ‘working towards the expected standard’, ‘working at the expected standard’ and ‘working at greater depth than the expected standard’. Any score between 80 and 99 is ‘working towards the expected standard’, between 100 and 109 is ‘working at the expected standard’ and a score from 110 to 120 is ‘working at greater depth than the expected standard’. How Scaled Scores and Standardised Scores interact This is where some interpretation of the two different types of scores is necessary. Head teacher Michael Tidd notes that standardised tests which report using Standardised Scores are different to statutory End of Key Stage tests which report Scaled Scores saying that, ”while only 50% of children can score over 100 on the standardised test, around ¾ can – and do – on the statutory tests.” As Michael notes, “Scoring 95 on one year’s standardised test is no more an indicator of SATs success than England winning a match this year means they’ll win the World Cup next year.” We do have some data which helps to understand the interaction between Scaled Scores and Standardised Scores. Data analyst Jamie Pembroke has produced blogs on converting the 2017 and 2018 KS2 scaled scores to standardised scores, the latest of which suggests that a Standardised Score between 90 (most generous) to 95 (least generous) is – very roughly – likely to be similar to a Scaled Score of 100. Rising Stars (producers of PIRA, PUMA and GAPS tests) suggest a Standardised Score of 94 and above indicates ‘working at the expected standard/greater depth’. They also suggest that ‘Greater Depth’ is indicated by a Standardised Score of 115 and above. What should Databusting Schools do? Broadly, schools should use Standardised Tests where possible to generate unbiased pupil performance data. This data can then be used (alongside the various other sources of information) in discussions about children’s development. Administering Standardised Tests should generally be done in Year 3 and above, and – unless you have a particular reason to do so – it should be done no more than once a year. Children in each cohort should then be placed into three broad groups:

All of these groups should be expected to make good progress through good classroom teaching. Children in Group C will generally need additional targeted support, with the aim where possible of moving into Groups B/A over time. The cut-offs for each of these groups are broadly as follows:

With interesting noises coming from Ofsted, Primary Schools are thinking more and more about what progress and attainment actually mean for their school, and what they should be doing to ensure that they have a sensible system for monitoring children’s development as they move through school. Using Standardised Scores to generate unbiased indications of a children’s relative performance, and grouping children into three broad categories each year, will help schools to build up a picture of a child’s relative performance over time. Linking Standard Scores to the standards expected at the end of key stage is not without issues, but can help Databusting schools to direct their resources to best support the children in their care.

1 Comment

Following the publication of Databusting for Schools in July, I've continued to travel the country raising awareness and understanding of data in education. I held a Masterclass at the EduTech show at Olympia in London, which was titled 'An Insiders Guide to the Numbers in School'. This focused on the use of standardised scores, and the understanding of the mathematics behind these incredibly useful statistics. I also spoke at the School Data Conference, leading a workshop on effectively analysing and interpreting data within a primary school, and led a session for North Lincolnshire Primary Heads Consortium.

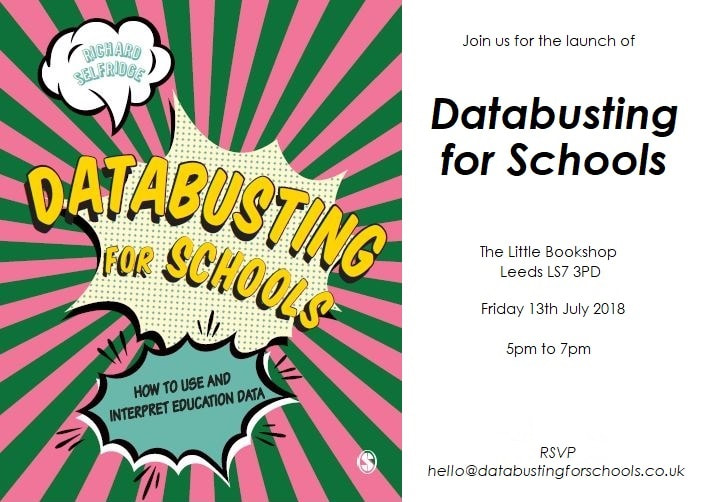

Exploring standardised scores, which I covered in depth in Databusting for Schools, has been well received at conferences; the presentation I did at researchEd's national conference ('Assessment 101 – Ten things everyone should know about assessing children') will be repeated at researchEd Durham later this month (details here), and I've written a blog for CEM which was published this week. The piece for CEM highlights the insight which standardised scores can give you over and above raw test scores: "If a student scores 65% on a test, what does this tell you? Is this mark good? Bad? Average? If it is deemed to be a good/bad/average mark, against whom is this judgement being made – the other children in a class, in a school, or similar children across the country? These fairly obvious questions are what led to the development of Standardised Scores; numbers which not only tell you how a child performed in a test, but also give you some information as to where their score sits within the range of scores recorded by other children who have taken the same test. So, if a child scored 65% on a test in which the average child scored 70%, their score might be reported as a standardised score of ‘95’; if the average child scored 60%, their score might be reported as ‘105’. If you know that standardised scores are created such that the mean score is allocated a score of 100, that two in three standardised scores are between 85 and 115, and that 95% of scores are between 70 and 130, you can make much more sense of a child’s test score reported as a standardised score than you can from a test result reported as a percentage or a raw score." With the growing move to understand the benefits and limitations of data in education, including extremely useful insights into the national picture from Ofsted's Towards the education inspection framework 2019 and the DfE Teacher Workload Advisory Group's Making Data Work report. I'm continuing to run sessions on the current pupil performance data landscape, looking at the recent history and future direction of the use of numerical data in schools. Please get in touch if you have any comments, feedback or requests for further information.  Following the publication of Databusting for Schools in July, the book is proving to be extremely popular, and feedback continues to come in. Databusting for Schools was written to make the world of education data accessible to those who may might the subject daunting, so my favourite bit of feedback so far is probably from Primary headteacher Darren Norman: 'Not dry at all, would highly recommend to leaders and governors'. That was exactly the aim for the book, and it's good to see that it is being received so well. I spoke at the ResearchEd National Conference in September, in a session which I called 'Assessment 101 – Ten things everyone should know about assessing children'. This session took various themes covered in Databusting for Schools and laid them out for those new to the issues in psychometrics. These kinds of introductions to assessment are proving to be very popular, as are the sessions I run on the current pupil performance data landscape, looking at the recent history and future direction of the use of numerical data in schools. I'm speaking at a couple of public events in October, if you like to hear me talk. EducTech Show, London Olympica, October 12th (details here). School Data Conference, London, November 7th (details here). ResearchEd Durham, Durham, November 24th (details here). I also wrote a piece, 'Tracking Pupil progress Doesn't Always Mean Using Data' for Teach Primary, which you can find here. As my Teach Primary piece concludes, "Many schools have stopped allocating dubious numbers to children, embracing standardised tests and comparative judgement instead. Lots have embraced the idea that assessing attainment and monitoring progress are separate endeavours, and have worked hard to ensure that children are properly supported in learning those things they have not yet mastered, rather than pushed on before they have grasped the curriculum appropriate to their age. When Sean Harford, Ofsted’s engaging national director of education, recently tweeted that tracking pupil progress “doesn’t necessarily mean ‘use data’”, the odd hissing sound you might have heard probably came from the offices of those who have been tasked with managing data in their schools, as the air slowly leaked from the tyres of their data juggernauts. Simply put, progress happens when a child’s knowledge and understanding advances, rather than when a number has been generated. It’s about what children can do now that they couldn’t do before, not simply whether the figures have changed. That, more than anything, is progress." Please get in touch if you have any comments, feedback or requests for further information. Much excitement here as we approach the official launch of Databusting for Schools, my new book for Sage Publications. And where better to launch a book for schools than the best children's bookshop in Leeds, The Little Bookshop? The lovely people at The Little Bookshop have agreed to open late especially for the launch, so put 13th July 2018 in your diary and join us as we celebrate.

The books is available for pre-order at all good bookshops, and the Big Online Shop even has a preview of chapter one for your delight and delectation. So, please spread the word, and join us if you can on the 13th July. Drinks and nibbles will be available, copies of book will be available for you to buy and all are welcome. Why not bring the children and make a night of it? RSVP at [email protected] and let us know you are coming! Well, this is exciting. Databusting for Schools is in final pre-production and is now available for pre-order on all good book websites and from all good booksellers. To celebrate the publication of the book, we will also be hosting book launches in London and Yorkshire. If you'd like to come along, please get in touch.

With things moving quickly in the world of education data, look out for updates and additional material on this website, as we continue the drive to look behind the numbers in education. In the meantime, here's a sneak preview from Chapter 1 of Databusting for Schools... "Schools have, of course, gathered data for a long time. The use of numerical data in schools has, however, increased massively in the last forty years. There are a number of reasons for this, from the increase in affordable computing power to ever-increasing external involvement in the internal workings of schools. Whatever the explanation for the rise in the use of numbers in schools, teachers, senior managers, governors and others working in and with schools are finding that they are being required to gather, analyse, interpret and act on numerical-based data as part of their roles in education. For many working in and with schools, this has required a level of understanding of numbers, and of statistics based on those numbers, which asks a great deal of busy professionals whose main focus is on education, not data. This book aims to give you a readable grounding in the use and interpretation of educational data throughout the education system. Aimed at the general reader, the book takes as its starting point those teachers, middle leaders and governors who are getting to grips with data. Those senior leaders who entered teaching before the current data-focused era will also find the ideas set out here invaluable in understanding many common misconceptions about numbers, as well as the many ways in which numbers can provide valuable insight into effective (and ineffective) practice in schools. The gathering, analysis and interpretation of numerical data is key to making sensible decisions about future courses of action. Since the decisions we make in schools have impacts not just on our students, but on the whole school community, we need to understand the new educational data landscape so we can decide how to move forward. In the modern world, Databusting has become essential." Databusting for Schools is available for pre-order at Amazon, Wordery and all other reputable booksellers. |

Richard SelfridgeA Primary Teacher who writes, discusses and talks about education data. Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed